Many Christian traditions connected with marriage are considered holy

writ but are not found in the Bible. Rather, they are

remnants of a pagan culture—ancient Athens—which was a radical democracy (for male citizens only),

decidedly idolatrous, and, relevant to the current gender issue, a slave-owning society.

For instance, the practice of women taking their husband’s

names at marriage is not a biblical practice, yet the worst accusation Beverly

LaHaye could find to level against Lucy Stone, a leader of the conservative

wing of women’s suffrage and the first American woman who refused to take her

husband’s name after marriage, is the fact that she refused to merge her legal

identity with that of her husband by taking his name.[1] DeMoss

also criticizes women for not to taking a husband’s name.[2] Today,

within some evangelical and fundamental Christian communities, women who

wish to preserve their own legal identities are libeled as “feminists”—meaning

they are considered to be in rebellion against God and drifting away from

Christian morality.[3]

But how are such accusations

justified when the practice of name changes after marriage can be traced

directly to a pagan culture in which a woman was required to change her name

whenever she changed households, whether

or not the change had to do with marriage? If an Athenian woman’s father

died and she was placed under the guardianship of a maternal uncle, her name automatically

changed to reflect that of her uncle. If her guardian happened to be a

non-relative, the results were the same. Her name changed each time she permanently changed households. At no time during

their lives were Greek women considered autonomous adults, and it did not

matter how many times a Greek woman had to change households, her name changed each

time to reflect that of the male head of household.[4]

There is no scriptural basis for

stigmatizing Christian women who choose not to align themselves with the laws

of ancient Athens. And it is to the scriptures that we appeal as our authority

in these matters.

Women in the Bible, always retained their pre-marriage identities

just as their husbands did. Marriage did not obliterate the individual

public/legal identities of biblical women. Rather, their marital status added to their identities rather than diminish

them. Yet, in spite of biblical evidence to the contrary, female name changes

after marriage continue to be patterned after the laws of a pagan culture that

left its women with no identities aside from that of the males in whose

households they resided.[5]

Even the practice of joining the name of husband and wife through hyphenating

is a legal identity change (usually done by the wife but not the husband), and therefore a compromise with Athenian law which

necessitated an identity change for wives.

Despite these historical facts [which have no connection with scripture], modern women who are not inclined to change their names

after marriage are often pressured to do so from the men they marry, from

pastors and spiritual leaders, from public opinion, and even after marriage, from marked silences

observed at introductions, and from disapproving attitudes and subliminal

messages coming from those closest to them. But where is scriptural precedence

for this? Changing a woman’s name originated as an ownership issue; what is it about the tradition that makes it holy?[6]

The honored tradition of “giving the bride away” comes from ancient Athenian

culture as well, and had everything to do with guardianship, citizenship, social/political success, and material prosperity--and nothing to do with fatherly love. To ensure the production of legitimate offspring, freeborn Athenian

women were literally given away by

their kyrios (lord) through legal

contract. It is oxymoronic that these freeborn women were considered prized

possessions. The reason for this was that only Athenian [male] citizens could

participate in the public life of the polis

(the Greek city-state), thereby ensuring its continuance. Only free-born

Athenian women could provide the polis with these citizens. But the union between a

freeborn Athenian woman and a male citizen had to be of a specific sort in

order for their offspring to be considered legitimate, which was crucial to

citizenship and all future inheritance and opportunity. In order to ensure

legitimate offspring Athenian women had to be transferred from one kyrios to another. [7]

From an Athenian male’s point of view, the real value in

being married to a freeborn Athenian woman was that she was the only source of future citizens. The

success or failure of the Athenian culture, a culture so powerful its influence

is still felt today, hinged upon just one thing—citizens descended from

freeborn Athenian women passed from

one “lord” to another by legal contract. Just so the success or failure of

complementarianism hinges on the women.

Female subjection is the only thing

that can lay claim to making complementarianism work.[8] But just

because a thing can be made to work, does not make it right.

The wives of many Athenian citizens were essentially nothing

more than prized broodmares and head housekeepers.[9] Modern

women would be horrified to be thought of and treated as Athenian women were—human

chattel, property to be bargained for, and transferred from one kyrios to another through contract.[10] Yet

how many blushing brides today proudly listen to the words, “Who gives this woman…?” accepting the lie that

anyone has the right to either keep or give them?

The modern practice of having witnesses at our marriage ceremonies can also be traced to Athenian law where, “The sole purpose of witnesses was to ensure the

recognition of the progeny of the union as legitimate and therefore heirs of

the oikoi (family/household) from

which they had descended.” And quoting Demosthenes, Just writes, “No man in concluding a transaction of such importance…would have

acted without witnesses. This is the reason why we celebrate marriages…and call

together those who are closest to us, because we are dealing with no light affairs (italics added).”[11]

No, the affairs were not light; they were affairs upon which citizenship, inheritance,

livelihood, and social and political status, stood. If an Athenian man or woman

lost their citizenship, or was declared illegitimate (which accomplished the

same), their lives were catastrophically destroyed. The presence of witnesses was

crucial in attesting to the legality of any union between those claiming

Athenian citizenship.

Nineteenth century activists who criticized marriage laws

were not against the institution itself. They were rightfully campaigning

against the “vandal” laws that were associated with marriage.[12] These

laws plundered the properties, obliterated the legal rights, the identities,

and the very legal existences of

women as they entered into matrimony.

The Athenian city-state, from which so much of our language

and cultural traditions originate, was a radical democracy for freeborn men only. More importantly, regarding attitudes and laws concerning women, it was also a slaveholding

society. Some believe, regarding gender, that there is no minor connection

between the intrinsic attitudes of slaveholders and those of sexists. Historian, Roger Just,

wrote: “…lack of self control, incontinence,

physical indulgence, inebriation, sensuality, luxury, are reported as the

natural characteristics not only of slaves and of women but also of the barbaroi who lived beyond the bounds of

the civilized Greek world. It is part of the complex Athenian male

self-definition that barbarians are routinely characterized in their wildness

and in their luxury as being both

effeminate and slavish…It is this

opposition which is crucial, for on it turn the Athenian notions of freedom and

subordination, notions themselves grounded in Athens’ economical structure, in

the fact that it was a slave-owning

society. And here of course is the nexus between politics and the attributes of

gender; it is the opposition between those innately possessed of self-control

and those who lack it that ideologically renders women’s subordinated place

within the social structure of the [Greek] polis

a ‘natural’ one.” [13]

[1] Beverly LaHaye, The Restless Woman, 1984

[2] See footnote #13

[3] “Are you in transition

back to Christian morality, or are you drifting toward selfish feminism?” Beverly

LaHaye, The Restless Woman, 1984

[4] “A woman’s lifelong

supervision by a guardian, her kyrios

(lord), summarizes her status in Athenian law. She was not considered a legally

competent, autonomous, individual responsible for her own actions or capable of

determining her own interests.” Roger Just, Women in

Athenian Law and Life, Routledge, London and New York, 1989

[5] “Women are specified by their relationships with men (Schaps 1977).

Men are specified by their proper names….the normal practice was to refer to a

woman as so-and-so‘s mother, wife, sister, or daughter, and we know the names

of remarkable few of the many women mentioned in law-court proceedings.” Roger

Just, Women in Athenian Law and Life, Routledge, London and New York, 1989

[6] “A wife should no more take her husband's name than he should hers.

My name is my identity and must not be lost." Lucy Stone

[7] “She whom her father, or her homopatric brother or her grandfather

on her father’s side gives…to be a lawful wife, from her the children shall be

legitimate…Plato gives a much more extended list of male relatives who had the

right to give a girl in marriage…” Roger Just, Women in Athenian Law and Life,

Routledge, London and New York, 1989

The transferring kyrios could be her father,

brother, any male guardian, etc…He could also be her husband. Athenian husbands

could, and did, transfer wives to other men.

[8] “If the wife does not

fulfill her responsibility, it is almost impossible for the husband to fulfill

his.” Derek Prince, Husbands & Fathers,

Chosen Books, Grand Rapids, MI, 2000

[9] “We have hetairai for

pleasure, pallakai to care for our

daily bodily needs, and gynaikes

(Athenian women married to citizens by engue whose children were legitimate) to

bear us legitimate children and to be the faithful guardians of our households…”

Roger Just, Women in Athenian Law and Life, Routledge, London and New York,

1989

[10] “The marriages of a special class of women, epikleroi, or

‘heiresses,’ …were awarded to their father’s closest kin.” ibid

[11] ibid

“At all

events, the giving of a woman in marriage…involved

an immediate transfer of wealth to the woman’s husband.”(emphasis added) ibid

[12] “Theodore [Weld]

emphatically stated how pleased he was to refute the property laws, of the

time, which transferred the wife’s property to the husband as soon as they

married: “a vandal law,” he called it.” Ellen H. Todras, Angelina Grimke: Voice of Abolition, 1999

[13] Roger Just, Women in

Athenian Law and Life, Routledge, London and New York, 1989

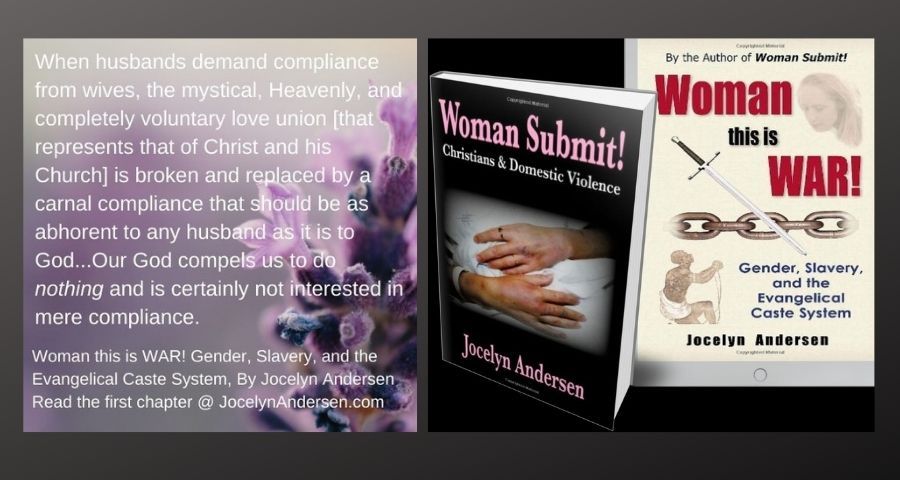

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of, Woman this is WAR! Gender, Slavery and the Evangelical Caste System.

Woman this is WAR!, examines Bible commentary and translation practices which have historically been androcentric (male centered) and even misogynistic (anti-woman).

These have adversely effected understanding of the scriptures, relations between women and men, the happiness of men and women, and, in general, has hindered the work of the gospel, by forbidding women to preach, pastor, or serve as elders or deacons. The book chronicles the early history of the women's rights movements, as well as the role of church leadership in aggressively suppressing both women's rights and the historical record of Christian initiatives within the movements.

Through the complementarian movement, many of the same arguments used to support the institution of slavery, are still used today in suppressing the rights of Christian women. This book documents identical arguments used by Christian leaders against both movements and is an unparalleled resource for all who desire an in-depth study of gender equality from a historical and Christian perspective.

This book traces history of women’s rights, much further than usual, to the very first feminists…who were Christians—godly women, who brought the issue of women's rights to the forefront as they struggled to alleviate the suffering of others, and found they were hindered in doing so for no other reason than the fact of their sex. This work, provides valuable historical insight into Christian initiatives in the movements for women’s rights, that are rarely included in Christian literature.

Woman this is WAR!, examines Bible commentary and translation practices which have historically been androcentric (male centered) and even misogynistic (anti-woman).

These have adversely effected understanding of the scriptures, relations between women and men, the happiness of men and women, and, in general, has hindered the work of the gospel, by forbidding women to preach, pastor, or serve as elders or deacons. The book chronicles the early history of the women's rights movements, as well as the role of church leadership in aggressively suppressing both women's rights and the historical record of Christian initiatives within the movements.

Through the complementarian movement, many of the same arguments used to support the institution of slavery, are still used today in suppressing the rights of Christian women. This book documents identical arguments used by Christian leaders against both movements and is an unparalleled resource for all who desire an in-depth study of gender equality from a historical and Christian perspective.

This book traces history of women’s rights, much further than usual, to the very first feminists…who were Christians—godly women, who brought the issue of women's rights to the forefront as they struggled to alleviate the suffering of others, and found they were hindered in doing so for no other reason than the fact of their sex. This work, provides valuable historical insight into Christian initiatives in the movements for women’s rights, that are rarely included in Christian literature.